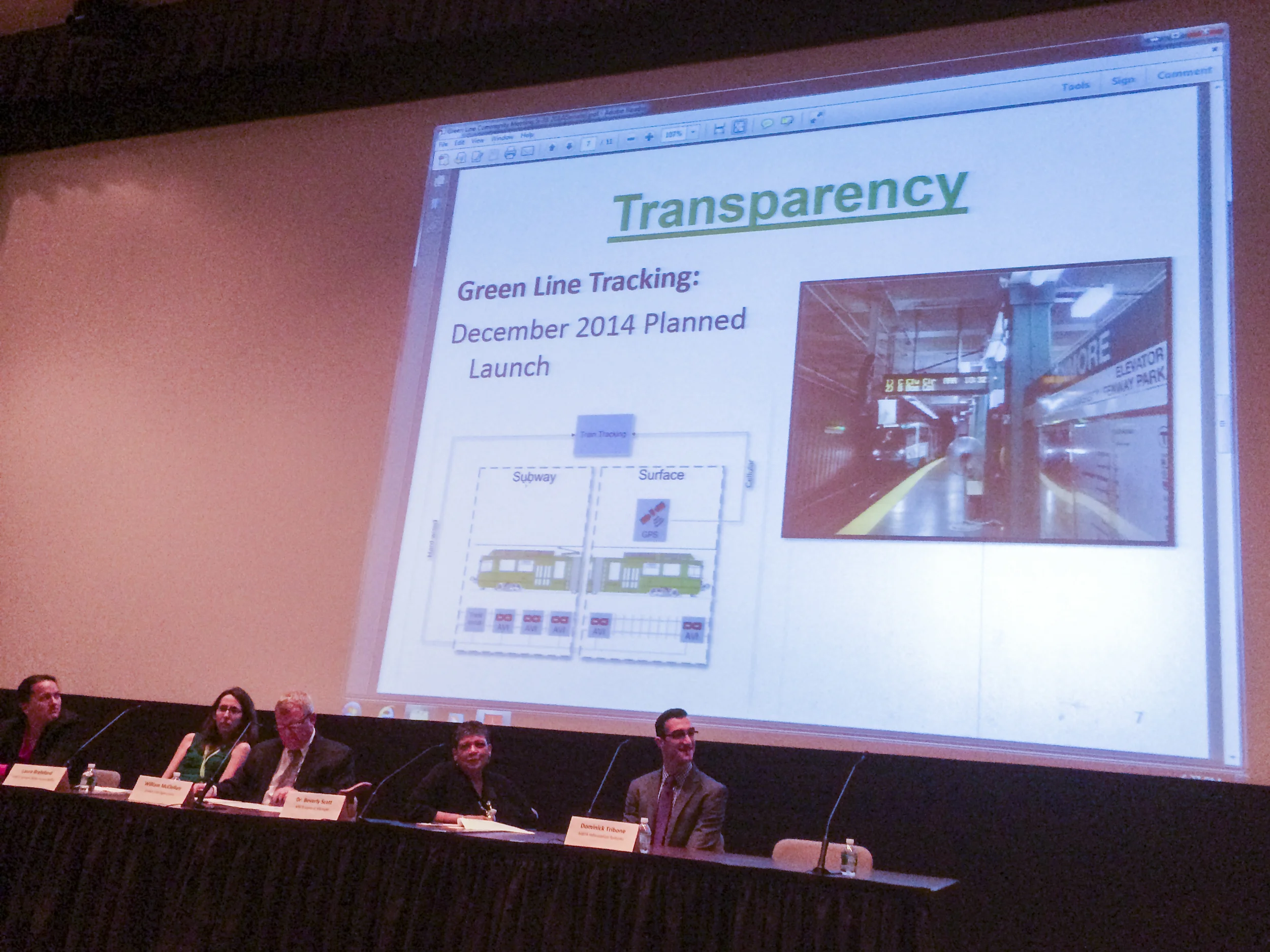

Back in June, I had the pleasure of attending a forum on Green Line issues hosted by the MBTA and facilitated greatly by Senator Brownsberger. The presentation included updates on the primary issues afflicting the Green Line and its dependent riders as outlined by Brian Kane, MBTA Director of Policy, Performance Management & Process Re-Engineering and former budget analyst with the MBTA Advisory Board.

Get a Backbone! Cut the Bulls**t Off-Street Parking

Boston has a strange way of committing to walkability, transit accessibility, and the adjustment of cultural expectations for parking per Menino's claim that 'the car is no longer king in Boston'. A large number of transit-oriented developments in and around Boston come with a lot of parking and even more is about to be built at a development that could've easily done without it.

Boston has a strange way of committing to walkability, transit accessibility, and the adjustment of cultural expectations for parking per Menino's claim that 'the car is no longer king in Boston'. A large number of transit-oriented developments in and around Boston come with a lot of parking and even more is about to be built at a development that could've easily done without it.

When news about a parking-free development in Allston started making the rounds in January, many in the neighbourhood vehemently argued against the development with the fear of increased parking pressures that we've come to expect of public comment in Boston.

Saying that the building won't have any parking is very disingenuous. The project was originally submitted to the Boston Redevelopment Authority[PDF] with the plan to have six parking spaces for car sharing services (e.g. Zipcar or Hertz Connect). Instead, the development was approved with 35 parking spaces.

Paul McMorrow nails the issue right on the head in his Globe editorial:

Nearly every developer who has ever tried to build in Boston has run into neighborhood interference over parking. Bostonians will shiv anyone who threatens to dilute the supply of free on-street parking. It’s the city’s job to calm these fears, and strike a balance between neighbors and developers, who cover the astronomical costs of building off-street parking by collecting inflated rents. This balancing act shouldn’t be as delicate as it once was, since city-dwellers are now far less married to their cars. But it’s still up to the city to make parking regulations catch up to the market.

[Sebastian] Mariscal’s Allston development isn’t overreaching at all by zeroing out cars entirely. It’s in a part of town that will undergo a dramatic transformation over the next decade, thanks to New Balance’s New Brighton Landing development. Mariscal’s building site is three blocks from a planned commuter rail stop. It’s a 10-minute walk from the Green Line. These are hardly insurmountable distances. And the market for car-free housing is far greater than Mariscal’s doubters believe. More than half of Boston residents currently take the T, bike, or walk to work. There are now 27,000 more car-free workers living in the city than there were a decade ago. Gathering 44 of them in one building should be a layup. Getting the city’s blessing to do so should have been, too.

The concerns about increased parking pressures were, as usual, not quantified or contested despite the fact that our apartment-dwelling urbanites are re-learning how to share, car sharing significantly reduces car ownership or the potential to own a car, and a shit ton of parking will be dumped on the area when New Balance's New Brighton Landing is finished. Add to that the state's commitment to a new commuter rail stop to…mitigate the need for parking? Wait, what’s going on here?

As noted in New Balance's submitted project documents, there's already a 1,200 space parking garage for the existing development and all new parking will be provided on-site. So a new commuter rail station is being put in, but we're still anticipating a need for larger amounts of parking?

The BRA's own vision for the area is inspiring and talks about developing a walkable, transit-oriented neighbourhood, but their recommendations for transportation improvements talk more from the perspective of improving car throughput and access to the Mass Pike and leave transit improvements to the hopeful increase of bus service and eventual arrival of a commuter rail station.

Parking and the availability of it in future developments further dramatically affects transit use and the effectiveness of transit, even with increased frequency of service, despite promising to increase the area's 'traffic' throughput. In fact, it's the sheer volume of car traffic that already chokes the existing roads and, in turn, transit service. More parking will only serve to give more people the option to drive.

The area's debilitating automobile traffic is a major reason why the 57 and 57A are late at least 35% of the time, which likely is disproportionately felt by the majority of riders who use the bus during rush hours. The 64, which directly serves the New Balance site and runs past Mariscal's 37 North Beacon St, is late almost 40% of the time.

This isn't to say service can't be improved in spite of additional parking, but no plans have been revealed so far to include dedicated bus lanes or other forms of transit prioritization to improve the reliability of the existing bus service. Without it, the area will remain auto-dependent and people will continue opting to drive and sit in traffic rather than wait for late and crowded buses.

And it's not just in Allston...

Similar visions of parking-loaded 'transit-oriented' developments have been approved immediately next to the new Yawkey Station that will also see increased commuter rail service and adjacent the new Assembly Square station on the Orange Line. The Assembly Row development in Somerville was approved with 10,066 spaces[PDF] while the Fenway Center development at Yawkey will see a more reasonable 1,290 spaces. Millennium Tower at Downtown Crossing, within walking distance of every transit line and commuter rail line in Western Massachusetts, has even been approved with 550 spaces despite thousands of public parking spaces in the neighbourhood that empty out after business hours, 822 of which sit in my office building across the street.

Fenway Center's numbers are still disproportionate to the need of the area considering its transit accessibility that will only increase over time and the further parking volume promised from other new and approved developments. The perception seems to be that Fenway games need more parking despite the fixed number of seats in the ballpark and the new two-platform commuter rail stop that will see full-time service once complete. Exacerbating neighbourhood traffic by making it more convenient to people to drive to ball games and the growing number of posh restaurants in Fenway isn't a great way to convince those very neighbourhoods that development is good.

These are all examples of transit-related capital investments being made by the state, MassDOT/MBTA, being undermined by the BRA approving adjacent 'transit-oriented' developments with large volumes of parking. While in some of these projects, the parking can and probably will be converted to other uses if/when the spaces go underutilized, but that alone is an expensive venture and the inclusion of parking into the development already increases its base cost. This increased cost translates into less housing and higher rents for those fewer units that get built.

But it can get better...

While there's not much that can be done to reduce the volume of parking at these already approved developments, the BRA, Boston Transportation Department, and MBTA can do a much better job of talking to each other in future developments about the real generator of automobile traffic: parking.

Instead of imposing parking 'guidelines', which act more as legal parking minimums, the BRA could offer 'parking credits' for developers to apportion parking off-site in existing parking structures. This would encourage more developers to build less expensive housing that would more effectively address Boston's severe housing crunch.

Additionally, the new developments don't necessarily need 1:1 or even 1:2 parking ratios because of a significant latent demand for housing without parking and the ability to address travel needs by improving the reliability of transit. Parking 'needs' can and will be further driven down by increasing the number of amenities and affordable, modern office spaces in the area, practically inherent in the act of increasing density with new development.

What else can we do with less expensive developments? Well, we can encourage developers to include modern civic and municipal spaces into new buildings. The city can even create new revenue with forward-thinking land use deals instead of selling the property outright for a one-time cash infusion. This further adds to the number of amenities within walking distance to new and existing developments and increases the livability and value of our neighbourhoods.

Again, it all comes down to our transportation choices when we have the opportunities to remake our cities block-by-block. 'When I design a building, the first thing I have to resolve is my parking,' Mariscal notes, just as every other developer before him and any to follow. By beefing up transit and actually treating it like the lifeblood of our city, we can reduce the pressure on developers to design parking into their buildings and the cost of our rent. In time, Bostonians will learn put down their shivs and not have a conniption over each development proposed without or with little parking when there's transit nearby just waiting to be improved. The BRA isn't helping by not doing its due diligence and addressing resident concerns with reason.