Celebrating 10 Years Of Advocacy: TransitMatters Exposes MBTA’s Nearly $7M Mistake With Auburndale Station

The T was not only about to continue neglecting Newton riders, it was about to degrade service for riders on the entire Framingham/Worcester Line.

For the next five weeks, we will be highlighting landmark moments in our history so far. Next up: Our exposure of the T’s nearly $7 million mistake with Auburndale Station.

Photo credit: “Auburndale station (MBTA)” Wikipedia page

All of Newton’s Commuter Rail stations—Auburndale, West Newton, and Newtonville—currently only have single-side, low platforms. Before the 1960s, Auburndale had a station designed by H.H. Richardson and landscaped by Frederick Law Olmsted (pictured right). In 1961, the state demolished the station and two out of four tracks for the MassPike extension into Boston. On top of being inaccessible, having a platform on just one side of the tracks means it is not possible to serve passengers in both directions throughout the day. For years, the Commuter Rail has neglected riders by leaving large gaps in service to Newton.

Responding to advocacy for an accessible Commuter Rail station in Newton from residents and Representative Kay Khan, the MBTA began redesigning Auburndale Station in the late 2000s. The T initially redesigned the station with mini-high platforms due to wide freight rights, but this did not impress the community. The T went back to the drawing board, and nothing public-facing happened with Auburndale Station for about five years.

Then in 2016, there were rumors that the MBTA would finally do something with the station. In February 2017, the T presented the final Auburndale Station design to the community. The T's new plan continued to have just one platform, but now on the opposite track. However, the T didn't plan to move other single-platform stations in Newton to the opposite track. Consequently, the MBTA planned to spend 58% of the total project cost on new switching equipment for trains to swap tracks between stations. To make matters worse, the T failed to confirm whether it was possible to maintain the Framingham/Worcester Line's schedule with trains swapping tracks in Newton.

Photo credit: Miles in Transit

The T was not only about to continue neglecting Newton riders, it was about to degrade service for riders on the entire Framingham/Worcester Line. Two TransitMatters members called attention to this issue at a public meeting for the final design. The T said it hadn't checked with railroad ops.

After a few months of TransitMatters raising the alarm about Auburndale, then-Secretary of Transportation Stephanie Pollack scrapped the design and sent the MBTA back to the drawing board in May 2017.

In 2019, the T revealed their new plan to build accessible platforms on the opposite track at all three Newton Commuter Rail stations and expected the final design in the spring of 2022. The MBTA's newest design would still cause large gaps in service Commuter Rail for Newton. However, in 2021, the T changed course and committed to building two-platform, accessible stations at all three Newton Commuter Rail stations!

The MBTA's Accessibility Initiatives report from June 2023 reported that Auburndale, West Newton, and Newtonville Stations are approaching 75% design. According to this report, the MBTA should complete the final design by February 2024. However, the MBTA has still not identified a source of funding for constructing the stations. The T will not be able to afford three full station rebuilds under the current capital funding constraints. This is one of the many reasons why the T needs more funding and a dedicated funding source.

Banner Photo Credit: Leslie Anderson/THE BOSTON GLOBE

Green Line Update Teases Improvements Enabled by Tracking Technology

Back in June, I had the pleasure of attending a forum on Green Line issues hosted by the MBTA and facilitated greatly by Senator Brownsberger. The presentation included updates on the primary issues afflicting the Green Line and its dependent riders as outlined by Brian Kane, MBTA Director of Policy, Performance Management & Process Re-Engineering and former budget analyst with the MBTA Advisory Board.

As a corollary to our guest contributor post on the disappointing improvements and issues with Commonwealth Avenue, we have a few (much delayed) updates about the T's more progressive plans to improve transit along the corridor.

Back in June, I had the pleasure of attending a forum on Green Line issues hosted by the MBTA and facilitated greatly by Senator Brownsberger. The presentation included updates on the primary issues afflicting the Green Line and its dependent riders as outlined by Brian Kane, MBTA Director of Policy, Performance Management & Process Re-Engineering and former budget analyst with the MBTA Advisory Board.

Others present at the meeting included leading MBTA staff that Dr. Scott heralded as subject matter experts to ensure questions could be answered directly by the most appropriate person from the agency. Top MBTA management included:

Dominick Tribone for questions on information systems

Bill McClellan, Director of Green Line Operations

Laura Brelsford, Deputy Director of System-Wide Accessibility

Melissa Dullea, Director of Planning & Schedules

Mr. Kane broke down the issues into 5 key areas and highlighted the improvements the T is aiming to tackle over the long run.

Speed

The biggest hindrances to speed right now are the incredible closeness of stops on some lines, the lack of signal preemption, and restrictions from fare collection and public outcry about boarding policies.

At the moment, the C line is the slowest, averaging 11.1km/h (6.9mi/h) with an average stop spacing of about 305m (1000 ft), while the D is the fastest, averaging 30.6km/h (19.5mi/h) with an average stop spacing of about 1.2km (4,000 ft).

Stop Consolidation

The number of stops increases time the train spends either stopped or slower than cruising speed. Even if the volume of passengers stays the same, the math still works out to be that the train spends more time slowing down to stop at each stop. Further, each stop that a train has to make before a stop light increases the chances that the train will miss a number of green cycles and get stuck at a red light. Of course, the real culprit of slow loading times is a capacity issue, which we'll discuss below. Ultimately, the promise is faster train speeds at the compromise of increasing the walking distance for some.

Brian Kane commented that the MBTA has championed stop consolidation before, but the issue is as polarising as the issue of fare collection. A survey in 2005 showed widespread support for stop consolidation while seemingly as many people come out to defend the need for a stop as the people who clamor to remove it. At the moment, there are no plans to make further consolidations, but monies have been issued for a Commonwealth Ave improvement scheme. Dr. Scott underscored the fact that part of the money earmarked for the project is in danger of expiring, so it needs to happen soon. The MBTA is in talks with BU about potential streamlining along the corridor.

Fare Collection

This has been one of the hottest button issues that has plagued the T, transit advocates, and the public at large. We could fill a whole post about fare collection issues alone. The long and short of it is that everyone wants two things:

collection of fares from everyone

all doors boarding

The solution is something everyone else seems to have solved outside of Boston: proof of payment (POP). The cool kid on the block right now is San Francisco's MUNI, who implemented the first system-wide POP deployment in the US...in 2012 - yes, all trolley lines and buses permit all-doors boarding.

POP was brought up multiple times in the meeting with respect to addressing the public's outcry to close the budget hole of fare evasion before turning to the public for more funding. The MBTA's response was to force front door boarding on all Green Line trains outside of rush hour and the issue was polarising.

As Mr. Kane underscored, the MBTA did exactly what people complained about in budget hearings. The front door policy makes it harder for the people to evade fares. However, those people are costing the T at most less than 1% the total $400 million in fares collected annually, much less the total $2 billion annual budget. We've talked about fare evasion here before.

Dr. Scott added that at some point the cost of countermeasures to minimise the loss from fare evasion starts to cost more than the nearly immeasurable actual losses from fare evasion. To punctuate that, I added that some transit agencies elsewhere account for losses from fare evasion as the cost of business.

At the moment, the T neither has the funding to increase the number of fare inspectors nor the funding to add fare collection equipment at all doors on the Green Line, as was done in San Francisco. In the long run, the vision is to replace the fare collection system completely, ideally in favour of a contactless payment system already embedded into many debit and credit cards today. The T will eventually join the increasing number of systems, including TfL in London and CTA in Chicago, that are making the move away from standalone fare collection systems that require them to effectively act as banks to manage rider transactions. This has been one of Dr. Scott's biggest long-term goals from day one and has come up in MBTA ROC meetings a number of times.

Currently, some Green Line stations do have fare validation machines, but to most passengers, it's not clear what they do.

Dr. Scott also offered to continue the conversation about fare collection and boarding policies through a broader charette to envision an end goal and actionable steps to achieve that vision (ideally of system-wide POP for the T).

Signal Preemption/Traffic Signal Priority

One of the major projects for the T is the upcoming tracking system, which will be launching in December of this year and cost a mere $13.5 million. This is a fraction of the cost of a full-blown train protection and control system that was last estimated to cost over $770 million at full build-out.

However, the current upgrade promises location awareness of Green Line vehicles sooner rather than later. Once we have a live, automated system that tells us where Green Line trains are, the MBTA can then start better spacing and management of trains, passengers will finally know roughly when their trains are coming, and most importantly we'll be able to tell the lights to change when a train is approaching. This is the miracle of traffic signal priority or traffic signal preemption.

The MBTA is working very closely with BTD and the city of Brookline's transport department to examine the impact of and ensure the success of traffic signal preemption once the automated vehicle location (AVL) system is switched on. The AVL will be able to communicate with Boston's centralised traffic management computers the location of trains. As trains approach an intersection with a green light, it can request that the light be held green for a little longer to let the train through. As trains approach an intersection with a red light, it can request that the red be shortened to let the train go through sooner.

Frequency

Frequency is a function of speed and volume of vehicles available. If vehicles can travel faster and there are more of them, naturally trains will pass any given point on the line more frequently.

At the moment, frequency is largely bound by the number of trains in the fleet. There are currently 215 individual Green Line cars at the moment. 86 of the oldest trains, are going out for overhauls to improve reliability and ensure they can continue running through the first quarter of the 21st Century. The first of the overhauled trains will arrive this autumn and they will continue to arrive through the autumn of 2016. The biggest passenger-facing changes in the overhaul will include:

conversion of all lighting to LED

new seats and interiors

ADA-compliant door warnings and signals

improved heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems

As recently announced, the MBTA will also be getting new trains, designated Type 9, for additional capacity. They will also help maintain the current level of frequency in spite of the additional distance trains will have to cover for the Green Line extension through Somerville as it comes online between 2017 and 2019. Ultimately, all Green Line cars except for the Type 9 cars are provisioned to be replaced as part of the Governor's Way Forward plan.

Capacity

If frequency is dependent on speed and fleet size, capacity is dependent on frequency and fleet size. It is a measurement of the overall volume of people who can be moved at peak travel times.

As mentioned, the Type 9s will be adding capacity to the system. Additionally, 8 cars that have been out of service in the long term are part of the 86 older cars that are being refurbished; this will add just a bit more capacity to the overall number of trains available for service.

However, the fleet capacity itself is limited until we have someplace to put the new trains. A new yard needs to be constructed to store and maintain the trains the T is buying. This is why the Type 9 trains won't be arriving until the Green Line extension's first phase is completed in 2017 since that part of the extension will include a new yard for Green Line trains in Somerville.

3-Car Trains

The Green Line's capacity is also limited by the power system. The current power systems that pump electricity through the Green Line's trolley wires aren't powerful enough to run 3-car trains close together. Since 3-car trains can't be run close together, you end up with the same effective capacity of three normal-sized 2-car trains at their regular frequency.

The MBTA is currently planning a study on the power systems of the Green Line in conjunction with the Red and Orange lines to figure out exactly what equipment needs to be replaced or added.

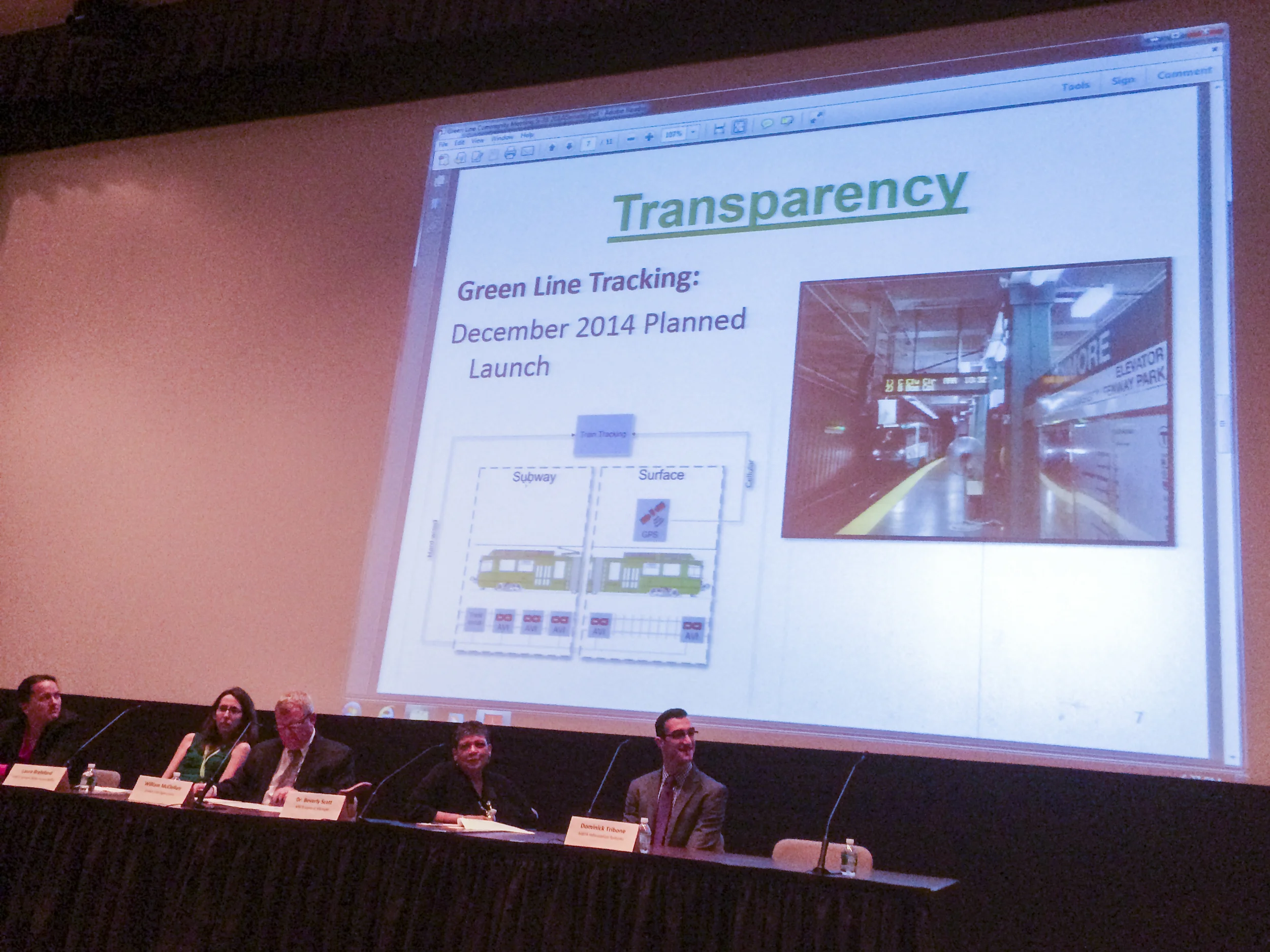

Transparency

As a bonus from the installation of the $13.5 million tracking system, riders will be able to see when their trains are actually coming, satisfying the long-time feature request of Bostonians since the late 20th Century.

Again, the Green Line tracking system will go live in December of 2014. In 2015, the T will go live with train time predictions

Accessibility

Station upgrades are being completed as the original round of ADA projects comes to completion. These have included a number of projects and are culminating in the 2-year renovation of Government Center station.

The T is already ramping up plans for a second round of projects to further improve accessibility of stations, including a number of Green Line stations. Financing has yet to be dedicated to this second set of accessibility projects, but will likely follow the release of cost estimates as the T closes in on the scope of the projects they want and need to include.

This second set of projects is also a perfect opportunity to adjust station placement for better service. In particular, stations that are currently placed on the near-side of intersections can be moved to the opposite side of the intersection. This would complement signal preemption since trains would be able to cross the intersection to a stop on the far-side instead of having to stop before the light to pick up passengers regardless of whether the light is green or not.

Comm Ave: from auto mile to people mile

Nearly a century ago, Commonwealth Avenue from Kenmore Square, heading west to Packard's Corner, was home to over a hundred automobile dealers and associated vendors. For much of the twentieth century, while riding the trolley, you would have passed showroom after showroom, parking lot after parking lot, all calling out for you to buy a car and drive away.

Contributor: Matthew Danish

ALLSTON — Nearly a century ago, Commonwealth Avenue from Kenmore Square, heading west to Packard's Corner, was home to over a hundred automobile dealers and associated vendors. For much of the twentieth century, while riding the trolley, you would have passed showroom after showroom, parking lot after parking lot, all calling out for you to buy a car and drive away.

Problems with this street have been known for decades. As the Brighton Item noted in 1948:

Something has to be done with Commonwealth Avenue, the broad and landscaped parkway that is perhaps Allston-Brighton's handsomest thoroughfare and undoubtedly its most lethal one. Multi laned, well paved, and alluring to the motorist made fretful by the cold molasses in Boston's ever cooking traffic jam, it is the Circe of highways.

In 2014, much has changed. We now know that people who are walking, biking and riding the T along Comm Ave strongly outnumber [PDF] the drivers. For example, for the area just west of the BU Bridge, the breakdown comes out as 7 to 3 in favor of non-car modes.

|

Time criteria |

Mode |

Count |

Percentage |

|

Peak Hour |

Green Line "B" |

2887 |

30.9% |

|

|

Car |

2780 |

29.8% |

|

|

Walking |

2507 |

26.9% |

|

|

Biking |

609 |

6.5% |

|

|

57 Bus |

364 |

3.9% |

|

|

BU Shuttle |

182 |

2.0% |

|

|

Total |

9329 |

100% |

Almost all of the automobile businesses have left, and the buildings have been largely converted into other uses. At long last, the city has produced plans for the second phase of the long awaited street reconstruction of Comm Ave, Phase 2A from Amory Street to Alcorn Street:

But these plans have turned out to be highly disappointing, by seemingly encoding the values of 1974 rather than 2014: with wider travel lanes goading higher automobile speeds, with sidewalk narrowing requiring the removal of older trees, with no provision for improved bicycle facilities on a busy corridor, and without addressing the problematic long blocks that impede pedestrian movement across the street.

A similar style plan has already been implemented for phase 1 of the corridor, from near Kenmore Square up to University Road. How did that turn out? Well, they added a lot of trees, brick crosswalks, and street furniture to make it look prettier. But the same problems that plague the phase 2A design also apply to the phase 1 design and we can see how it worked out: not well. The design of phase 1 has proven completely inadequate for handling the volume of pedestrians generated by Boston University in between classes.

The crossings of Comm Ave are not sufficient in number and are poorly timed for pedestrians. And the sidewalks have been narrowed by the addition of poorly thought-out street furniture zones to the point that the remaining space overflows with a flood of students between classes.

Even while the pedestrians are squeezed, the drivers are treated to a generous motorway with wide lanes and few interruptions. The various trees and fences create the sense of a divided highway, and the long blocks practically beg you to put the pedal to the metal.

As a result, phase 1 represented a triumph of aesthetics over sense and safety. The continuing trickle of car/pedestrian and car/bike collisions attests to the problem.

Fortunately, these collisions have been non-fatal (and therefore, it seems, non-newsworthy). There is typically some form of victim-blaming involved, "oh, why was he running across the street," without any consideration of how the poor street design creates the problem by encouraging higher car speeds, and by making it unnecessarily obnoxious for pedestrians to cross the street as needed.

So when I heard that the phase 2A design was mostly an extension of the phase 1 design further west on Comm Ave, I became alarmed. We missed our opportunity to fix the obvious problems with phase 1. We should not miss it again. But the city was very secretive about phase 2A. The only public meeting, at 25% design, was held in March of 2012, and poorly advertised as usual. Various advocacy organizations, including LivableStreets, did submit letters with suggestions that would have greatly improved the design. But nothing was heard in response.

Actually, the only reason we heard anything at all is because the city suddenly filed plans in December of 2013 with the tree warden to have the remaining in-scope, older trees removed. So two years after the comment letters were submitted, we finally learned that basically nothing was taken into consideration and the 75% design remained mostly the same in principle. The trees were to be taken away and the sidewalk narrowed with essentially no community input or process. We also learned that no further process is planned. The design of phase 2A has been funded by Boston University and they are not interested in making anything but the most minor of changes.

This is simply unacceptable. I understand that Boston University is a major abutter to the street. I appreciate that they have been willing to provide funds. They have put together a decent transportation master plan. I know that they care about their students' safety, even if I believe that they are mistaken in their methods. But if they expected to simply drop a design on the city without public input, without a chance to fix the obvious problems with it, without incorporating modern pedestrian- and bicycle-friendly street design, then they are wrong and must be challenged by members of the community.

In short, LivableStreets and I believe the following changes must be made to the design of Comm Ave phase 2A:

- Minimize sidewalk narrowing, make intersections pedestrian friendly, and extend curbs.

- The travel lanes must not be widened, instead they must be calmed to reduce speeds.

- Additional crossings of the street must be added to cut up the long blocks.

- Integrate with the MBTA plans to consolidate stations and add signal priority.

- Comm Ave is a designated cycle-track on the bicycle network plan, and that begins now.

What you can do:

- Please sign LivableStreets' online postcard to add your name and a short message about why you care about Commonwealth Avenue

- Contact your elected officials at the city and the state level

- Let the Boston Transportation Department know your concern about the city's commitment to its Complete Streets guidelines

Categories

- Children (1)

- Diversions (1)

- Olympics (1)

- MAPC (2)

- Red–Blue Connector (2)

- Urban Design (3)

- Bus (4)

- Fares (4)

- Late Night Service (4)

- MBTA ROC (4)

- Silver Line (4)

- Snow (5)

- Blue Line (8)

- Emergency (8)

- Orange Line (8)

- Public Comment (8)

- Maintenance (9)

- Operations (9)

- Signage (9)

- Fare Collection (10)

- Labs (11)

- Safety (11)

- Planning (12)

- Communication (14)

- MBCR (14)

- MassDOT (14)

- Green Line (16)

- History & Culture (16)

- Red Line (18)

- MBTA Bus (21)

- Commuter Rail (24)

- Advocacy (26)

- Capital Construction (28)

- Politics (30)

- Podcast (35)

- News (38)

- Media (40)

- Funding (42)

- Statements (50)

- MBTA (57)